Wendy Carlos in her home studio, 1979. Photo Credit: Leonard M. DeLessio, Getty Images.

The best ideas are the ones that seem obvious after the fact. Such was the case with Wendy Carlos’ analog synthesizer recording of J.S Bach works, Switched-On Bach. The idea: make the first ever electronic music album that people would actually like.

Composer/performer Wendy Carlos and producer Rachel Elkind created a work that blew open the doors for an entire generation of composers and listeners. Switched-On Bach was an album that proved the artistic value of the analog synthesizer not only to the classical world, but to the entire musical mainstream. That’s right, Wendy Carlos became the forerunner of modern electronic music and one of the most important anti-establishment musicians in history—by playing Bach.

Because of Wendy Carlos, one could say that Bach is responsible for Deadmau5. Photo credit: WideFuture.

Before Switched-On Bach, it was rare to find people who even knew how to pronounce the word synthesizer, let alone understand what one was. If asked, most people would probably say it was a machine for making laser sounds. Or maybe it was a computer? A repurposed telephone switchboard? It was anybody’s guess. The synthesizer was an instrument that would change the course of electronic music forever, but in the 1950s - early 60s, it was tainted with misunderstanding and distrust. And who was to blame for this? Turns out it was the classical music world.

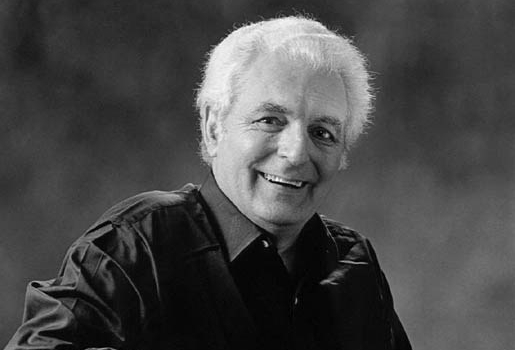

One of Wendy Carlos’ professors at Columbia was electronic pioneer Vladmir Ussachevsky, who termed the choice values for envelope generators: Attack, Delay, Sustain, & final Release values (ADSR). Photo credit: Bruce Duffie.

Back in the day, the only institutions that could afford synthesizers were those of the classical establishment, and the instrument couldn’t have been in worse hands. Music was knee-deep in an age of “integral serialism,” during which classical values as basic as tonality were thrown by the wayside in favor of mathematical (and often atonal) methods of music composition. This new line of thinking also enveloped the early schools of electronic music. Composer/conductor Pierre Boulez best defined the movement’s purpose as “to annihilate the will of the composer in favor of a predetermining system.”

Basically, synthesizers were exclusively in the hands of musicians who were philosophically opposed to making crowd-pleasing music. For this reason, the majority of works released in the electronic music genre were heard as robot noises and glorified sound effect collages, at least in the general public’s opinion. And really, they weren’t far off.

An excerpt from Morton Subotnick’s critically acclaimed electronic music album, Silver Apples of the Moon.

While studying music and physics at Brown University and composition at Columbia University, Wendy Carlos found herself squarely at odds with the classical standards of her time. Even electronic music, the subject she thought would give her relief from the snobbery of classical, was similarly filled with pretension and “musical snake-oil.”

Despite all this, Carlos still believed that electronic music’s potential was greater than what the classical establishment had planned. In 1966, Carlos purchased her own Moog synthesizer (its pronounced /moʊɡ/ MOHG, by the way). With Moog being an infinitely smaller company than it is today, the synth was hand-delivered by Robert Moog himself. The customizable unit that was sold to her came with just one cabinet and a few modules, which Carlos added to extensively throughout the years.

Carlos and Moog met at an Audio Engineering Society meeting in NYC a few years before her Moog purchase. The two would remain life-long friends. Photo credit: Polar Music Prize.

As Carlos got more acquainted with the Moog and its capabilities, she began to understand the variable ways that it could be improved. This began a years-long correspondence with Robert Moog in which they discussed and even co-produced mechanical upgrades to the Moog synthesizer. Having studied the intricacies of early electronic music as well as physics, Wendy Carlos was a musician that knew how to put a nail to a hammer. Robert Moog himself was a brilliant engineer and a student and appreciator of music. “It was a perfect fit,” Carlos would later say. “He was a creative engineer who spoke music; I was a musician who spoke science.”

Among the innovations that Carlos and Robert Moog co-produced were the first velocity-sensitive keys for electronic keyboards. Photo credit: Wendy Carlos, Switched-On Boxed Set.

After a couple years of tinkering and using the Moog for small commissioned works, Carlos began thinking about recording her first full album. She started this project with the help of producer Rachel Elkind, whom she previously met through a friend at her job at Gotham Recording studios. Carlos recalls that it was “loathe at first sight,” but after a year of continued pestering, Elkind agreed to work on a project with her.

Elkind wasn’t impressed with the Moog, not at first anyway. Trying to sway her opinion, Carlos performed two Moog-styled covers for Elkind: “What’s New Pussycat” and Bach’s “Two-Part Invention in F Major.” While the first piece didn’t amaze, Elkind found promise in the Bach arrangement. Though it was Carlos’ hope to record an album of her own compositions, Elkind convinced her that the best chance an all-synthesizer album had to succeed commercially (as the instrument was still unfamiliar to general listeners) was to feature more well-established music like Bach’s. Elkind believed that the music of the album “…had to sing and dance and had to have truth, and if it did, then it would speak to an audience.”

Wendy Carlos has repeatedly referred to Rachel Elkind as “the brains” behind Switched-On Bach. Photo credit: Wendy Carlos.

And as it turned out, the Moog synthesizer was a perfect match for Bach—not because of what it could do, but precisely because of what it couldn’t do. Early synths like the Moog were monophonic, meaning they could only play one note at a time. Pianistic chords were not an option. A sustained, connected melody line wasn’t possible either. Considering these limitations, the contrapuntal and staccato sounds of Baroque music were a perfect fit for the Moog.

The production of Switched-On Bach took place in Carlos’ home studio in the spring and summer of 1968. Carlos notes that Elkind’s contributions on the album are greater than what most people give her credit for, emphasizing an interview in which Elkind stated, “I’m a real tyrant, and go for the moment more than anything. And I think that Wendy is a better performer because of it. If there’s any criticism of our music, it’s that it’s over-polished, and I try very hard to work against that instinct to over-polish, which is inherent to the kind of music we do. The synthesizer is very unforgiving.” Additional technical hurdles included the synth’s tendency to go out of tune, having to record pieces one note and one line at a time, and having to manually switch between hugely variable patch cord formations to achieve different sounds.

Towards the end of production, Elkind reached out to a contact she had at Columbia Records in hopes of getting the album signed to the label. Luckily, Columbia was in the midst of a “Bach-to-Rock” marketing campaign, for which Switched-On Bach was a perfect fit. Because Columbia knew the album was basically finished and that they wouldn’t have to pay the two unknown artists much money, they saw producing the record as a low-risk venture.

Much to Columbia’s surprise, Switched-On Bach was an instant hit. Just as Elkind had planned, the familiarity of Bach mixed with the mysterious but alluring sound of the Moog synthesizer made Switched-On Bach a massive crossover success. Robert Moog joked that the album was the first “real” demonstration of synth music, saying “You know what real music is for the record industry? Music that makes real money!” Switched-On Bach went on to become the first ever platinum-selling classical album and won three Grammys including “Best Classical Album.” The record peaked at No. 10 on the Billboard 200, passing (for a brief moment) The Beatles’ White Album.

The Switched-On Bach album cover. Photo credit: Wendy Carlos, Switched-On Boxed Set.

Although it was a pop sensation, the classical world was also hard-pressed to find fault with Carlos’ bold new work. Disregarding the flare of the synthesizer, the album was an incredible demonstration of technical keyboard proficiency. This was in part thanks to musicologist Benjamin Folkman, who consulted on the album to make sure that Carlos’ performance practices fell in line with the baroque idioms of Bach’s time.

A month before Switched-On Bach’s release, Robert Moog brought the album to a presentation at an Audio Engineering Society meeting (AES). As he hit play on Carlos’ recording of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G Major, Moog saw “people’s mouth’s dropping open.”Wendy Carlos, who was in attendance, was given a standing ovation.

Classical gatekeepers had an even harder time hating on the album when one of its most dedicated fans came forward publicly—Glenn Gould. By phone and mail, the legendary Bach interpreter actively went out of his way to tell his colleagues and friends about the accomplishment of Switched-On Bach, later calling it “the record of the decade.”

Switched-On Bach corroborated Gould’s longtime belief that the future of music would depend less on live performance and more on the advancement of recording technology. Photo credit: Fred Plaut, Musicology Now.

The number of musicians that picked up the Moog because of Switched-On Bach’s success was astronomical, and included artists as influential as Stevie Wonder, Isao Tomita, and even The Beatles. Perhaps the most important adopter of the synth in the wake of Carlos was Keith Emerson, who got his hands on a Moog as quickly as possible after hearing Switched-On Bach in a record store. Soon after, Keith started Emerson Lake & Palmer, using the Moog as the defining characteristic of the band’s sound. Emerson Lake & Palmer then spearheaded the progressive-rock movement, leading to everything from Brian Eno to video game music.

Directly inspired by Switched-On Bach, Keith Emerson became the first major musician to take the Moog synthesizer on tour. Photo credit: Ed Perlstein, Getty Images.

With all this in mind, I think it’s time we start giving more credit where credit’s due. Wendy Carlos’ work on Switched-On Bach re-introduced the world to electronic music, solidified the synth as an instrument of extraordinary potential, and served as the bed-rock for musicians that would make the music world what it is today. Switched-On Bach needs be recognized as a watershed event, an invention of the light bulb, a moment in history where there was before and after. Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Elvis shaking his hips on the Milton Berle Show, Bob Dylan performing “Maggie’s Farm” at the Newport Folk Festival—and Wendy Carlos using Bach as a catalyst to start an electronic revolution.

Wendy Carlos in her home studio with her Chocolate Point Siamese cat, Pandy, 2007. Photo credit: Wendy Carlos.

If you’re looking to satisfy your Bach and technology needs this month, La Follia and Golden Hornet have you covered! On April 7th, La Follia Austin Baroque will be holding the last concert of their all-Bach season, performing Bach’s A Minor Violin Concerto, Triple Concerto, and E Major Harpsichord Concerto with guest harpsichordist Anton Nel.

On April 12th, Golden Hornet and Alamo Drafthouse Cinemas are teaming up with Thinkery to host Thinkery 21: Listen Up!, featuring artists, musicians, scientists and designers who explore sound in innovative ways. See a special preview of Golden Hornet’s upcoming album, The Sound of Science—music inspired by and reflective of the scientist’s life and practice, and visit with KMFA at our booth!